Written by Ikeh Akinyemi✏️

JavaScript’s reputation as a single-threaded language often raises eyebrows. How can it handle asynchronous operations like network requests or timers without freezing the application?

The answer lies in its runtime architecture, which includes the call stack, Web APIs, task queues (including the microtask queue), and the event loop.

This article will discuss how JavaScript achieves this seemingly paradoxical feat. We’ll explore the interworking between the call stack, event loop, and various queues that make it all possible while maintaining its single-threaded nature.

The call stack: JavaScript’s execution coordinator

JavaScript’s single-threaded nature means it can only execute one task at a time. But how does it keep track of what’s running, what’s next, and where to resume after an interruption? This is where the call stack comes into play.

What is the call stack?

The call stack is a data structure that records the execution context of your program. Think of it as a to-do list for JavaScript’s engine.

Here’s how it operates:

- Last-In-First-Out (LIFO) — Functions are added to the top of the stack and removed from the top once completed

- Execution context — Each function call creates a new context (e.g., variables, arguments) that’s pushed onto the stack

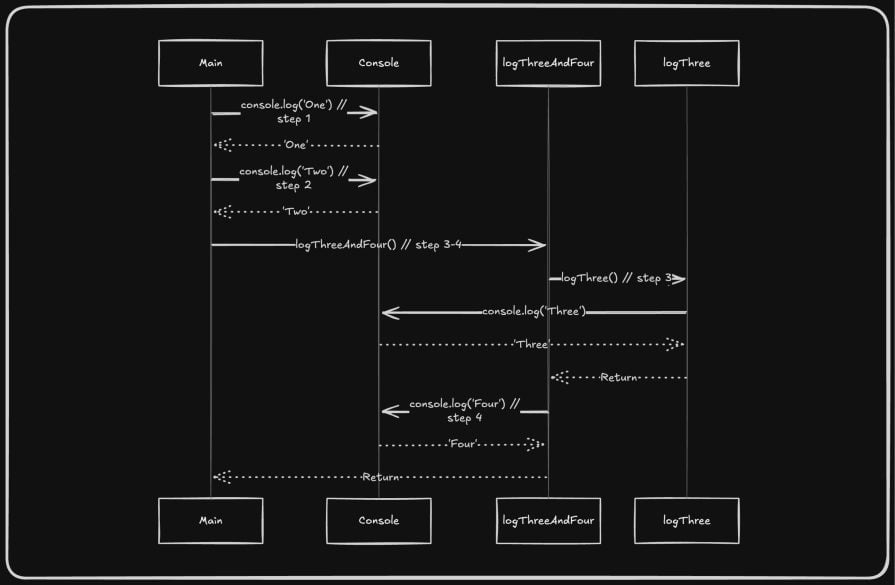

Let’s see how the call stack works by dissecting and following the execution path of the simple script below:

function logThree() {

console.log(‘Three’);

}

Function logThreeAndFour() {

logThree(); // step 3

console.log(‘Four’); // step 4

}

console.log(‘One’); // step 1

console.log(‘Two’); // step 2

logThreeAndFour(); // step 3-4

>```

In this walkthrough:

* **Stack** — Represents the current functions waiting to be executed, with the most recently added function at the top

* **Action** — Describes what the JavaScript engine actually does at each step, including executing functions and removing them from the stack

Here’s how the call stack processes the above script: **Step 1**: `console.log('One')` is pushed onto the stack:

* **Stack** — `[main(), console.log('One')]`

* **Action** — Executes — `'One'`, pops off the stack

**Step 2**: `console.log('Two')` is pushed:

* **Stack** — `[main(), console.log('Two')]`

* **Action** — Executes `'Two'`, pops off

**Step 3**: `logThreeAndFour()` is invoked:

* **Stack** — `[main(), logThreeAndFour()]`

* **Action** — Inside `logThreeAndFour(), logThree()` is called

* **Stack** — `[main(), logThreeAndFour(), logThree()]`

* **Action** — `logThree()` calls `console.log('Three')`

* **Stack** — `[main(), logThreeAndFour(), logThree(), console.log('Three')]`

* **Action** — Executes `'Three'`, pops off

* **Stack** — `[main(), logThreeAndFour(), logThree()]` → `logThree()` pops off

**Step 4**: `console.log('Four')` is pushed

* **Stack** — `[main(), logThreeAndFour(), console.log('Four')]`

* **Action** — Executes `'Four'`, pops off

* **Stack** —`[main(), logThreeAndFour()]` → `logThreeAndFour()` pops off

Finally, the stack is empty, and the program exits:

### The single-threaded dilemma

Since JavaScript has only one call stack, blocking operations (e.g., CPU-heavy loops) freeze the entire application:

```javascript

function longRunningTask() {

// Simulate a 3-second delay

const start = Date.now();

while (Date.now() - start < 3000) {} // Blocks the stack

console.log('Task done!');

}

longRunningTask(); // Freezes the UI for 3 seconds

console.log('This waits...'); // Executes after the loop

This limitation is why JavaScript relies on asynchronous operations (e.g., setTimeout, fetch) handled by browser APIs outside the call stack.

Web APIs & task queue: Extending JavaScript’s capabilities

While the call stack manages synchronous execution, JavaScript’s true power lies in its ability to handle asynchronous operations without blocking the main thread. This is made possible by Web APIs and the task queue, which work in tandem with the event loop to offload and schedule non-blocking tasks.

The role of Web APIs

Web APIs are browser-provided interfaces that handle tasks outside JavaScript’s core runtime. They include:

- Timers —

setTimeout,setInterval - Network requests —

fetch,XMLHttpRequest - DOM manipulation —

addEventListener,click,scroll - Device APIs — Geolocation, Camera, Notifications

These APIs allow JavaScript to delegate time-consuming operations to the browser’s multi-threaded environment, freeing the call stack to process other tasks.

How Web APIs and the task queue work together

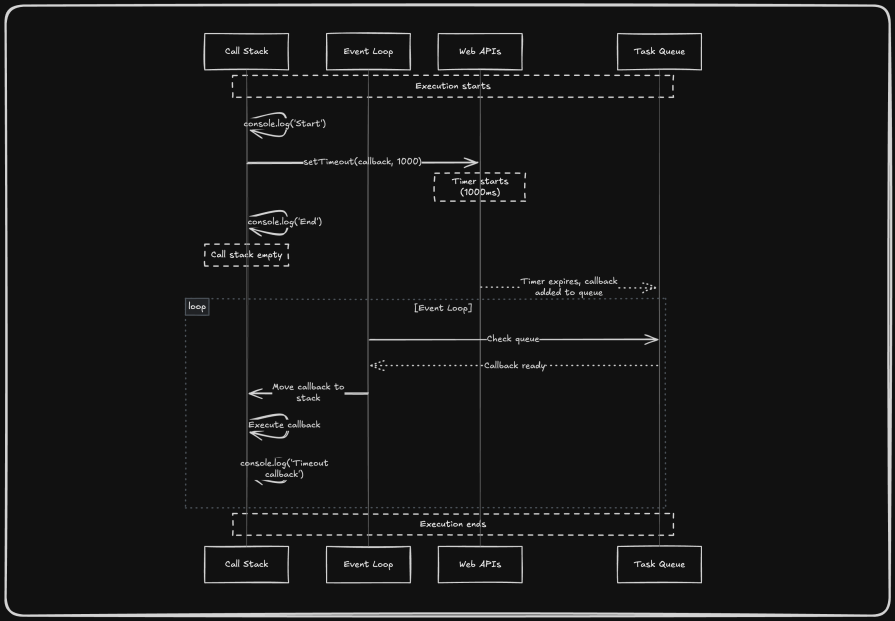

Let’s break down a setTimeout example:

console.log('Start');

setTimeout(() => {

console.log('Timeout callback');

}, 1000);

console.log('End');

Here’s the execution flow of the above snippet:

- Call stack:

-

console.log('Start')executes and pops off -

setTimeout()registers the callback with the browser’s timer API and pops off -

console.log('End')executes and pops off

-

- Browser background:

- The timer API counts 1,000ms

- Task queue:

- After the timer expires, the callback

() => { console.log(...) }is added to the task queue

- After the timer expires, the callback

-

Event loop:

- Once the call stack is empty, the event loop moves the callback from the task queue to the stack

-

console.log('Timeout callback')executes:

Start End Timeout callback```

Note that timer delays are minimum guarantees, meaning a setTimeout(callback, 1000) callback might execute after 1,000ms, but never before. If the call stack is busy (e.g., with a long-running loop), the callback waits in the task queue.

Let’s see another example using the Geolocation API:

console.log('Requesting location...');

navigator.geolocation.getCurrentPosition(

(position) => { console.log(position); }, // Success callback

(error) => { console.error(error); } // Error callback

);

console.log('Waiting for user permission...');

In the above snippet, getCurrentPosition registers the callbacks with the browser’s geolocation API. Then the browser handles permission prompts and GPS data fetching. Once the user responds, the relevant callback joins the task queue. This allows the event loop to transfer it to the call stack when idle:

Requesting location...

Waiting for user permission...

{ coords: ... } // After user grants permission

Without Web APIs and the task queue, the call stack would freeze during network requests, timers, or user interactions.

Microtask queue and event loop: Prioritizing promises

While the task queue handles callback-based APIs like [[setTimeout]](https://blog.logrocket.com/using-settimeout-timer-apis-node-js/), JavaScript’s modern asynchronous features (promises, async/await) rely on the microtask queue. Understanding how the event loop prioritizes this queue is key to mastering JavaScript’s execution order.

What is the microtask queue?

The microtask queue is a dedicated queue for:

- Promise reactions —

.then(),.catch(),.finally()handlers -

queueMicrotask()— Explicitly adds a function to the microtask queue -

**async/await**— A function call afterawaitis queued as a microtask - MutationObserver callbacks — Used to track DOM changes

Unlike the task queue, the microtask queue has higher priority. The event loop processes all microtasks before moving to tasks. The event loop follows a strict sequence of workflow. It executes all tasks in the call stack, drains the microtask queue completely, renders UI updates (if any), and then processes one task from the task queue before repeating the entire process again, continuously. This ensures promise-based code runs as soon as possible, even if tasks are scheduled earlier.

Let’s see an example of microtasks vs tasks queues:

console.log('Start');

// Task (setTimeout)

setTimeout(() => console.log('Timeout'), 0);

// Microtask (Promise)

Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log('Promise'));

console.log('End');

This produces the following output:

Start

End

Promise

Timeout

The breakdown execution follows the following sequence:

The breakdown execution follows the following sequence:

-

console.log('Start')executes -

setTimeoutschedules its callback in the task queue -

Promise.resolve().then()schedules its callback in the microtask queue -

console.log('End')executes - Event Loop:

- Call stack is empty → process microtasks

-

Promiselogs - Microtask queue is empty → process next task

-

Timeoutlogs

A common caveat with microtasks

Before continuing, it is worth mentioning a caveat that exists with microtasks. This has to do with nested microtasks; microtasks can schedule more microtasks, potentially blocking the event loop like below:

function recursiveMicrotask() {

Promise.resolve().then(() => {

console.log('Microtask!');

recursiveMicrotask(); // Infinite loop

});

}

recursiveMicrotask();

The above script will hang as the microtask queue is never empty, and the approach to fix this issue is to use setTimeout to defer work to the task queue.

async/await and microtasks

async/await syntax is syntactic sugar for promises. Code after await is wrapped in a microtask:

async function fetchData() {

console.log('Fetching...');

const response = await fetch('/data'); // Pauses here

console.log('Data received'); // Queued as microtask

}

fetchData();

console.log('Script continues');

The output is as follows:

Fetching...

Script continues

Data received

Web Workers: Offloading heavy tasks

JavaScript’s single-threaded model ensures simplicity but struggles with CPU-heavy tasks like image processing, and complex or large dataset calculations. These tasks can freeze the UI, creating a poor user experience. Web Workers solve this by executing scripts in separate background threads, freeing the main thread to handle the DOM and user interactions.

How Web Workers operate

Workers run in an isolated environment with their own memory space. They cannot access the DOM or window object, ensuring thread safety. Communication between the main thread and workers happens via message passing, where data is copied (via structured cloning) or transferred (using Transferable objects) to avoid shared memory conflicts.

The below code block shows a sample of delegating a complex work of processing an image that’s assumed in this scenario to take a lot of computational time to complete. worker.postMessage method sends a message to the worker. It then utilizes the worker.onmessage and worker.onerror to handle the success and error of the background work.

Here’s the main thread:

// Create a worker and send data

const worker = new Worker('worker.js');

worker.postMessage({ task: 'processImage', imageData: rawPixels });

// Listen for results or errors

worker.onmessage = (event) => {

displayProcessedImage(event.data); // Handle result

};

worker.onerror = (error) => {

console.error('Worker error:', error); // Handle failures

};

In the below code snippet, we utilize the onmessage method to receive the notification to start processing the image. The rawPixel passed down can be accessed on the event object through the data field as below.

And now we see it from the worker.js viewpoint:

// Receive and process data

self.onmessage = (event) => {

const processedData = heavyComputation(event.data.imageData);

self.postMessage(processedData); // Return result

};

Workers operate in a separate global scope, hence the use of self. Use Transferable objects (e.g., ArrayBuffer) for large data to avoid costly copying, and spawning too many workers can bloat memory; reuse them for recurring tasks.

Conclusion

JavaScript’s asynchronous prowess lies in its elegant orchestration of the call stack, Web APIs, and the event loop—a system that enables non-blocking execution despite its single-threaded nature. By leveraging the task queue for callback-based operations and prioritizing the microtask queue for promises, JavaScript ensures efficient handling of asynchronous workflows.

By mastering these concepts, you’ll write code that’s not just functional but predictable and performant, whether you’re handling user interactions, fetching data, or optimizing rendering.

Experiment with DevTools, embrace asynchronous patterns, and let JavaScript’s event loop work for you—not against you.

LogRocket: Debug JavaScript errors more easily by understanding the context

Debugging code is always a tedious task. But the more you understand your errors, the easier it is to fix them.

LogRocket allows you to understand these errors in new and unique ways. Our frontend monitoring solution tracks user engagement with your JavaScript frontends to give you the ability to see exactly what the user did that led to an error.

LogRocket records console logs, page load times, stack traces, slow network requests/responses with headers + bodies, browser metadata, and custom logs. Understanding the impact of your JavaScript code will never be easier!

Top comments (0)