Intro

In this post we will try and explain how the reactor works. In the previous posts we used it extensively to execute our futures but we treated it as a black box. It's time to shed some light on it!

Reactor? Loop?

A reactor is, in a nutshell, a loop. To explain it I think an analogy is in order. Suppose you have asked a girl/boy to a date using email (yes, I know, it's old-school). You expect an answer so you check your email. And check your email. And check your email. Until, finally, you get your answer.

Rust's reactor is like that. You give it a future and it checks over and over its state until completion (or error). It does that calling a function called, unsurprisingly, poll. It's up to the implementer to write the poll function. All you have to do is to return a Poll<T,E> structure (see Poll docs for more details). In reality the reactor doesn't poll your function endlessly but, for the time being, let's stop here and start with and example.

A future from scratch

In order to test our reactor knowledge we are going to implement a future from scratch. In other words we will implement the Future trait manually. We will implement the simplest future available: one that does not return until a specific time has come.

We are going to call our struct WaitForIt:

#[derive(Debug)]

struct WaitForIt {

message: String,

until: DateTime<Utc>,

polls: u64,

}

Our struct will hold the time to wait for, a custom string message and the number of times it has been polled. To help clean our code we are going to implement the new function too:

impl WaitForIt {

pub fn new(message: String, delay: Duration) -> WaitForIt {

WaitForIt {

polls: 0,

message: message,

until: Utc::now() + delay,

}

}

}

The new function will create and initialize a WaitForIt instance.

Now we will implement the Future trait. All we are required to do is to supply the poll method:

impl Future for WaitForIt {

type Item = String;

type Error = Box<Error>;

fn poll(&mut self) -> Poll<Self::Item, Self::Error> {

let now = Utc::now();

if self.until < now {

Ok(Async::Ready(

format!("{} after {} polls!", self.message, self.polls),

))

} else {

self.polls += 1;

println!("not ready yet --> {:?}", self);

Ok(Async::NotReady)

}

}

}

Let's go through it in steps. These awkward lines:

type Item = String;

type Error = Box<Error>;

are called associated types. They are meant to indicate what the future will return upon completion (or error). So we are saying: our will future will resolve into either a String or a Box<Error>.

This line:

fn poll(&mut self) -> Poll<Self::Item, Self::Error> {

Defines the poll function. The Self::Item and Self::Error parts are placeholders of the associated types specified earlier. In our case the method reads like: fn poll(&mut self) -> Poll<String, Box<Error>>.

Now our logic will be:

let now = Utc::now();

if self.until < now {

// Tell reactor we are ready!

} else {

// Tell reactor we are not ready! Come back later!

}

How can we tell the reactor we aren't finished yet? We return Ok with the Async::NotReady enum. If we are done we return Ok with Async::Ready(T). So our function becomes:

impl Future for WaitForIt {

type Item = String;

type Error = Box<Error>;

fn poll(&mut self) -> Poll<Self::Item, Self::Error> {

let now = Utc::now();

if self.until < now {

Ok(Async::Ready(

format!("{} after {} polls!", self.message, self.polls),

))

} else {

self.polls += 1;

println!("not ready yet --> {:?}", self);

Ok(Async::NotReady)

}

}

}

To run our future we have to create a reactor in main and ask it to run our future implementing struct.

fn main() {

let mut reactor = Core::new().unwrap();

let wfi_1 = WaitForIt::new("I'm done:".to_owned(), Duration::seconds(1));

println!("wfi_1 == {:?}", wfi_1);

let ret = reactor.run(wfi_1).unwrap();

println!("ret == {:?}", ret);

}

Now if we run it we expect our future to wait 1 second and then complete. Let's run it:

Running `target/debug/tst_fut_create`

wfi_1 == WaitForIt { message: "I\'m done:", until: 2017-11-07T16:07:06.382232234Z, polls: 0 }

not ready yet --> WaitForIt { message: "I\'m done:", until: 2017-11-07T16:07:06.382232234Z, polls: 1 }

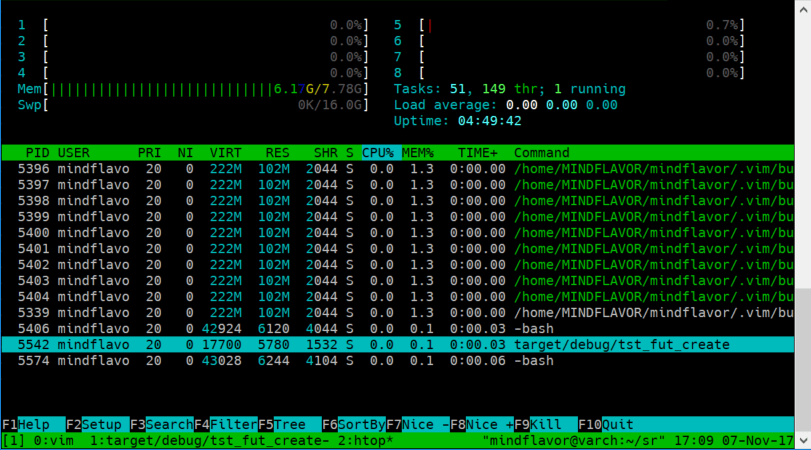

Aaaand... the code will be stuck. Also worth noting is that the process does not consume any CPU:

But why is that? That's the reactor magic: the reactor does not poll a parked function unless explicitly told so. In our case the reactor called our function immediately. We returned Async::NotReady so the reactor parked our function. Unless something unparks our function the reactor will never call it again. While waiting the reactor is basically idle so it does not consume any CPU as shown above. This yields great efficiency as we do not waste CPU cycles asking for completion over and over again. In our email example we could avoid checking the mail manually and wait for a notification instead. So we are free to play Doom in the meantime.

Another more meaningful example could be receiving data from the network. We could block our thread waiting for a network packet or we could do something else while we wait. You might wonder why this approach is better than using OS threads. Long story short, it is often more efficient.

Unparking

But how can we correct our example? We need to unpark our future somehow. Ideally we should have some external event to unpark our future (for example a keypress or a network packet) but for our example we will unpark manually using this simple line:

futures::task::current().notify();

So our future implementation becomes:

impl Future for WaitForIt {

type Item = String;

type Error = Box<Error>;

fn poll(&mut self) -> Poll<Self::Item, Self::Error> {

let now = Utc::now();

if self.until < now {

Ok(Async::Ready(

format!("{} after {} polls!", self.message, self.polls),

))

} else {

self.polls += 1;

println!("not ready yet --> {:?}", self);

futures::task::current().notify();

Ok(Async::NotReady)

}

}

}

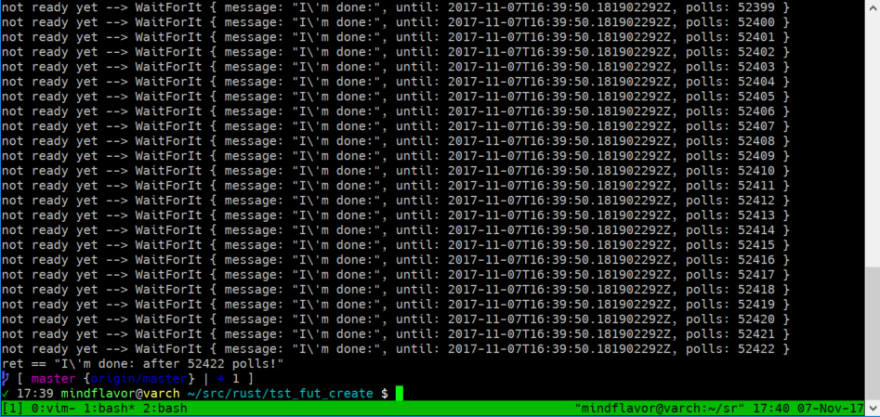

Now let's run the code:

Now the code completes. Notice that, in my case, the function has been called over 50k times in a second! That's a waste of resources and clearly demonstrates why you should unpark your future only when something happened. This is evident looking and the CPU consumption of our process:

Note also how the loop consumes only a single thread. This is by design and one of the sources of efficiency. You can, of course, use more threads if necessary.

Joining

An useful feature of reactors is the ability to run multiple futures concurrently. This is how we harness the efficiency of the single thread loop: when a future is parked, another one can proceed.

For this example we are going to reuse our WaitForIt struct. We just call it twice at the same time. We start creating two instances of our future:

let wfi_1 = WaitForIt::new("I'm done:".to_owned(), Duration::seconds(1));

println!("wfi_1 == {:?}", wfi_1);

let wfi_2 = WaitForIt::new("I'm done too:".to_owned(), Duration::seconds(1));

println!("wfi_2 == {:?}", wfi_2);

Now we can call the futures::future::join_all function. The join_all function expects an iterator with our futures. For our porpuses a simple vector will do:

let v = vec![wfi_1, wfi_2];

The join_all function returns, basically, an enumerable with the resolved futures.

let sel = join_all(v);

So our complete code will be:

fn main() {

let mut reactor = Core::new().unwrap();

let wfi_1 = WaitForIt::new("I'm done:".to_owned(), Duration::seconds(1));

println!("wfi_1 == {:?}", wfi_1);

let wfi_2 = WaitForIt::new("I'm done too:".to_owned(), Duration::seconds(1));

println!("wfi_2 == {:?}", wfi_2);

let v = vec![wfi_1, wfi_2];

let sel = join_all(v);

let ret = reactor.run(sel).unwrap();

println!("ret == {:?}", ret);

}

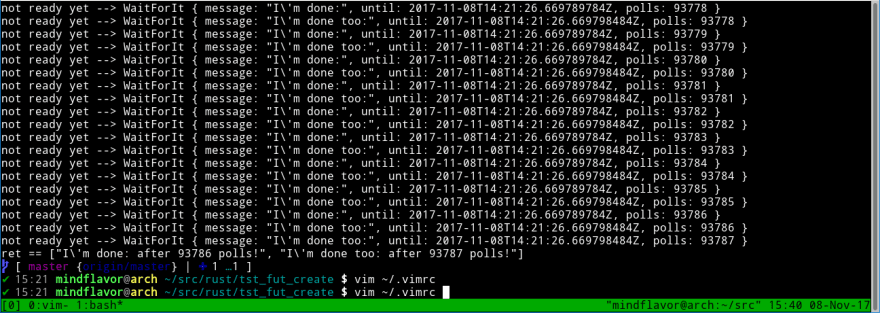

Now let's run it. The output will be something like this:

The key point here is that the two requests are interleaved: the first future is called, then the second, then the first and so on until both are completed. As you can see in the above image, the first future completed before the second one. Also the second one gets called twice before coming to completion.

Select

There are many more functions in the future trait. Another thing worth exploring here is the select function. The select function runs two (or more in case of select_all) futures and returns the first one coming to completion. This is useful for implementing timeouts. Our example can simply be:

fn main() {

let mut reactor = Core::new().unwrap();

let wfi_1 = WaitForIt::new("I'm done:".to_owned(), Duration::seconds(1));

println!("wfi_1 == {:?}", wfi_1);

let wfi_2 = WaitForIt::new("I'm done too:".to_owned(), Duration::seconds(2));

println!("wfi_2 == {:?}", wfi_2);

let v = vec![wfi_1, wfi_2];

let sel = select_all(v);

let ret = reactor.run(sel).unwrap();

println!("ret == {:?}", ret);

}

Closing remarks

In the part 4 we will create a more "real life" future: one that does not use CPU resources needlessly and behaves as expected when used in a reactor.

Happy coding,

Francesco Cogno

Top comments (2)

Hi

many thanks for that tutorial, really interesting! I just got one question:

You state the reactor parks our future in case we return

But here, you seem to notify the reactor to unpark before we return Ok(Async::NotReady):

So the reactor gets a notification to unpark something that's not yet been parked, doesn't it? ;-)

Ah yes it's true.

It's an horrible way of simulating the external unpark command :)

Ideally this command should be issued by another "entity" (for example the OS in case of async IO).