By: Peter Solymos

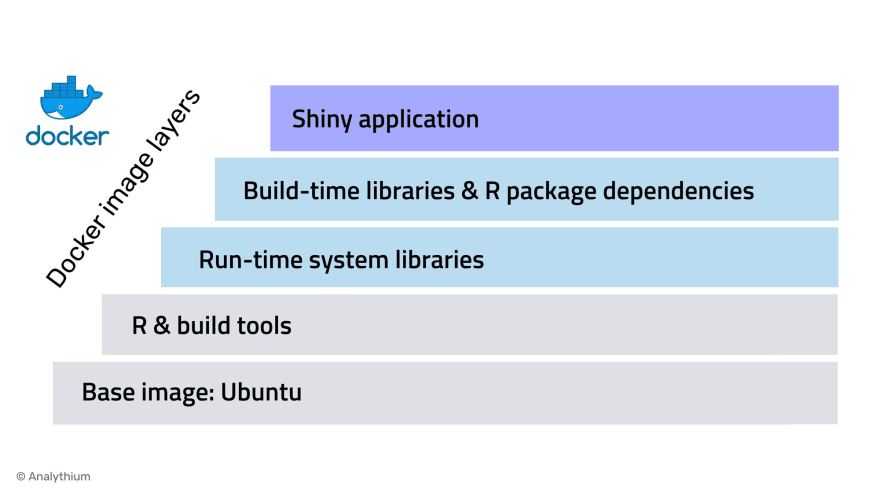

The use of Docker with R has been transformative in many

ways

over the past 5 years. What is common in this diversity of use cases is

that the Docker images almost always start with a parent image. What

parent image you use? How do you add new layers to it? These questions

will determine how quickly you can iterate while in development, and the

size of the final image you send to production. In this post, I will

compare using different parent images and outline best practices. I

focus on Shiny apps but most of these ideas apply generally to any

dockerized R application, like images for compute jobs or interfaces.

Parent images

In the previous post, we explored dependency management for Shiny

apps

using the rocker/r-ubuntu:20.04 as the parent image. A parent image is

an image that you define in the FROM directive of the Dockerfile. A

base image

has FROM scratch as the first line. The R base images start with

parent images. For example, the R Ubuntu image starts with

FROM ubuntu:focal.

Here are the four commonly used parent images for R:

docker pull rhub/r-minimal:4.0.5

docker pull rocker/r-base:4.0.4

docker pull rocker/r-ubuntu:20.04

docker pull rstudio/r-base:4.0.4-focal

The image sizes vary quite a bit with the Alpine Linux base

rhub/r-minimal being smallest and the Ubuntu-based rstudio/r-base

25x the size of the smallest image:

$ docker images

REPOSITORY TAG SIZE

rhub/r-minimal 4.0.5 35.3MB

rocker/r-base 4.0.4 761MB

rocker/r-ubuntu 20.04 673MB

rstudio/r-base 4.0.4-focal 894MB

The Debian Linux based rocker/r-base Docker image from the

Rocker

project is considered bleeding edge when it comes to system

dependencies, i.e. latest development versions are usually available

sooner than on other Linux distributions.

The two Ubuntu Linux based images, rocker/r-ubuntu and

rstudio/r-base from the

Rocker

project and from RStudio are for

long-term support Ubuntu versions and use the

RSPM CRAN binaries.

The Alpine Linux based rhub/r-minimal Docker image from the

r-hub project is preferred for its

small image sizes.

Using BildKit

Docker versions 18.09 or higher come with a new opt-in builder backend

called BuildKit. BuildKit prints out

a nice summary of each layer including timing for the layers and the

overall build. This is the general build command that I used to compare

the four parent images:

DOCKER_BUILDKIT=1 docker build --no-cache -f $FILE -t $IMAGE .

BuildKit backend is enabled by turning on the DOCKER_BUILDKIT=1

environment variable. I use the --no-cache option to avoid using

cached layers, thus having a fair assessment of build times (you usually

only build 1 and not 4). The -f $FILE flag allows building from

different files kept in the same folder.

All the code used here can be found in this GitHub repository, look in

the folder 99-images:

Image build times

This is the script I used to build the four images with BuildKit:

# rhub/r-minimal

export IMAGE="analythium/covidapp-shiny:minimal"

export FILE="Dockerfile.minimal"

DOCKER_BUILDKIT=1 docker build --no-cache -f $FILE -t $IMAGE .

# rocker/r-base

export IMAGE="analythium/covidapp-shiny:base"

export FILE="Dockerfile.base"

DOCKER_BUILDKIT=1 docker build --no-cache -f $FILE -t $IMAGE .

# rocker/r-ubuntu

export IMAGE="analythium/covidapp-shiny:ubuntu"

export FILE="Dockerfile.ubuntu"

DOCKER_BUILDKIT=1 docker build --no-cache -f $FILE -t $IMAGE .

# rstudio/r-base

export IMAGE="analythium/covidapp-shiny:focal"

export FILE="Dockerfile.focal"

DOCKER_BUILDKIT=1 docker build --no-cache -f $FILE -t $IMAGE .

I changed the CRAN repository for the Debian and Ubuntu Rocker images to

see timing differences between installing packages as binary or from

source. Total build times (on a 6-year old MacBook Pro) were the

following:

-

rhub/r-minimal: 27 minutes with building packages from source -

rocker/r-base: 12 minutes when building from source, 2.9 minutes when installing binary packages -

rocker/r-ubuntu: 12 minutes when building from source, 3.2 minutes when installing binary packages -

rstudio/r-base: 3.1 minutes with installing binary packages

The difference between the binary vs. source package installs is

expected. What is interesting is the 12 vs. 27 minutes between the

Debian/Ubuntu images and the minimal Alpine image. Is it worth waiting

for?

Image sizes

I got the image sizes from docker images and made a small data frame

in R to calculate the size difference between the final and parent

images:

x = data.frame(TAG=c("minimal", "base", "ubuntu", "focal"),

PARENT_SIZE=c(35, 761, 673, 894) / 1000, # base image

FINAL_SIZE=c(222 / 1000, 1.05, 1.22, 1.38)) # final image

x$DIFF = x$FINAL_SIZE - x$PARENT_SIZE

# TAG PARENT_SIZE FINAL_SIZE DIFF

# 1 minimal 0.035 0.222 0.187

# 2 base 0.761 1.050 0.289

# 3 ubuntu 0.673 1.220 0.547

# 4 focal 0.894 1.380 0.486

The image sizes themselves differed quite a bit, the RStudio Ubuntu

image was 6.2x larger than the minimal R image. Size differences were

similarly different.

Image sizes can be deceiving. It might not matter much if images are

large if for example, we have multiple images sharing some of the

layers

(i.e. ones from the parent image). The CPU and RAM footprint of the

containers might also be unrelated to the image sizes. But it might

impact "cold start" performance when images are pulled to an empty

server.

Alpine Linux based image

The Dockerfiles and the build experience for the Ubuntu and Debian

images were very similar. Build times and image sizes were also

comparable. The Alpine Linux-based minimal image took the longest time

to build but resulted in the smallest image size. The Dockerfile for

this setup also looks quite different from the Debian/Ubuntu setup:

FROM rhub/r-minimal:4.0.5

RUN apk update

RUN apk add --no-cache --update-cache \

--repository http://nl.alpinelinux.org/alpine/v3.11/main \

autoconf=2.69-r2 \

automake=1.16.1-r0 \

bash tzdata

RUN echo "America/Edmonton" > /etc/timezone

RUN installr -d \

-t "R-dev file linux-headers libxml2-dev gnutls-dev openssl-dev libx11-dev cairo-dev libxt-dev" \

-a "libxml2 cairo libx11 font-xfree86-type1" \

remotes shiny forecast jsonlite ggplot2 htmltools plotly Cairo

RUN rm -rf /var/cache/apk/*

RUN addgroup --system app && adduser --system --ingroup app app

WORKDIR /home/app

COPY app .

RUN chown app:app -R /home/app

USER app

EXPOSE 3838

CMD ["R", "-e", "options(tz='America/Edmonton');shiny::runApp('/home/app', port = 3838, host = '0.0.0.0')"]

The base image is so bare-bones that it needs to install time zones,

fonts and the Cairo device for ggplot2 to work (read the limitations

here). Instead of

apt you have apk and might have to work a bit harder to find all the

Alpine-specific dependencies.

One interesting aspect of this image is that instead of the littler

utilities familiar from the Rocker images, we have the very similar

installr script that installs R packages and system requirements:

- the

-dflag installs then removes compilers (gcc,musl-dev,g++), as these are typically not needed on the final image; - system packages listed after the

-tflag are removed after the R packages have been installed; - system packages listed after the

-aflag are run-time dependencies that are needed for the packages to function properly and are not removed from the image.

The installation of the system packages – that are all available on the

other parent images – contributes to the longer build times. The

BuildKit output gives you a clue about where exactly the time was spent.

The rest of the Dockerfile is very similar to the other distributions:

add Linux user, copy files, expose port, define the entrypoint command.

But how do you figure out what system packages you need?

System packages

First of all, each package lists its system requirements. These are

usually run-time dependencies that the package needs to properly

function. So check that first.

There are at least two databases listing package requirements: one

maintained by

RStudio (this

supports RSPM), another one by

R-hub. Both of these list system

packages for various Linux distributions, macOS, and Windows. But even

with these databases, the build- vs. run-time dependencies can be

sometimes hard to distinguish. Build-time system libraries are always

named with a -dev or -devel postfix. Read the vignette of the

maketools

R package by Jeroen Ooms for a nice explanation and a suggested workflow

for determining run-time dependencies of packages.

Best practices

Based on these results and the list of Dockerfile best

practices,

here are a few suggestions to improve the developer experience and the

quality of the final Docker images.

1. Minimize dependencies

Avoid installing "nice to have" packages and do not start from

general-purpose parent images aimed at interactive use. Images for Shiny

apps and other web services benefit from keeping the images as lean as

possible by adding those R packages and system requirements that are

absolutely necessary. Multi-stage

builds

can be helpful to only include artifacts that are needed.

2. Use caching

When building an image, Docker executes each instruction in the order

specified in the Dockerfile. Docker looks for an existing image in its

cache that it can reuse, rather than creating a new (duplicate) image.

Only the instructions RUN, COPY, ADD create layers:

- for the

RUNinstructions, just the command string from theDockerfileis used to find a match from an existing image; - for the

ADDandCOPYinstructions, the contents of the file(s) in the image are examined and a checksum is calculated for each file; - the last-modified and last-accessed times of the file(s) are not

considered in these checksums for the

ADDandCOPYinstructions.

3. Order layers

Caching can be useful is when installing R package dependencies. In a

previous post, we looked at how to use the renv

package

to install dependencies. Here is a simplified snippet from

that

Dockerfile:

## install dependencies

COPY ./renv.lock .

RUN Rscript -e "renv::restore()"

## copy the app

COPY app .

What would happen if we switched the two blocks?

## copy the app

COPY app .

## install dependencies

COPY ./renv.lock .

RUN Rscript -e "renv::restore()"

You would have to wait for the build to reinstall all the R packages

whenever the app files have changed. This is because once the cache is

invalidated all subsequent Dockerfile commands generate new images

instead of using the cache.

It is best to order the instructions in your Dockerfile from the less

frequently changed to the more frequently changed. This ensures that the

build cache is reusable.

4. Switch user

Running the container with root privileges allows unrestricted use which

is to be avoided in production. Although you can find lots of examples

on the Internet where the container is run as root, this is generally

considered bad practice. Use something like this:

RUN addgroup --system app \

&& adduser --system --ingroup app app

WORKDIR /home/app

COPY app .

RUN chown app:app -R /home/app

USER app

- Use linter

Best practices for writing Dockerfiles are being followed more and more

often according to this paper

after mining more than 10 million Dockerfiles on Docker Hub and GitHub.

However, there is still room for improvement. This is where

linters come in as

useful tools for static code analysis.

Hadolint lists lots of

rules for Dockerfiles and is available as a VS Code

extension.

Summary

This post started with a simple premise: compare the four most commonly

used parent images for R and draw some conclusions. It became a really

long post, but I believe it gives a good rationale for following a few

basic suggestions that can hugely improve the developer experience and

the quality of the final Docker images.

Top comments (4)

Great post. I am trying to build an image for a recent version of rstudio server using "fdewes/rstudio-server-arm64" as reference (yes, it is for raspberry pi).

Just got an error with NPM or YARN. After get it working I will need those tips in this article to make some cleaning and the "multi stage build" path.

Thanks! Not sure why you are getting NPM/YARN errors from that image build though.

Just got a working image ... need a time to implement the best practices, including "multi stage build"

github.com/pinei/edgyR-pi

Wow. You really made some progress there! That's really good to see. I am thinking of entering the Raspberry edge world myself, this'll be a good starting point for sure.