Introduction

Thank you for the overwhelming response to the first blog post on the rationale exploration for Blockchain Platform Architecture. In the first part, I discussed the basics of Distributed systems and their unreliability. However, when dealing with any system, architectural characteristics play a vital role in determining the system's quality. The ISO 25010 sets the standards of the quality characteristics that a software exhibits.

Performance and Scalability are two of the keystone qualities that make any large scale systems usable. Remember, if we had a large computer with infinite resources, there would not be any distributed systems. So, distributed systems, being so, must always be performant and should scale so as not run out of business.

However, a performant and scalable distributed system is anything but easy. There is a myriad of techniques to imbibe Performance and Scalability, each one always costing you something. Hybrid approaches do work but at the cost of complexity and manageability.

Enter the Block

Scale and Performance in a Blockchain no matter how complex and diverse a topic can always be started with the Block. Why?

Because it is the fundamental unit in a Blockchain that packs transactions. Imagine it like a medium to perform State Machine Replication of the database. It is similar to the economics of flying in business class versus economy. The difference is in the number of round trips when transactions need to be synced across nodes. Lesser the round trips, the more economical it becomes. The Block can contain transactions in the form of state changes. Each state change can be thought of as a set of key-value pairs proposed by users packed into a logical entity called a transaction.

Stitch 'em in a Chain

So why do we need a chain of Blocks? A chain of Blocks is a way to determine the integrity of the data on the network. We all are familiar with the dynamics of how a Merkle hash tree works. It works on the magic of trapdoors and randomness of Hash Functions. These characteristics are incredibly crucial in how we perceive the characteristics of Blockchain. In the real sense, the chain signifies the permanence of data built using a form of a singular thread of Blocks that is always growing outwards.

Ultimately, the hash's purpose is to establish a singular path from the leaf with the root ever-growing outwards.

To give Blockchain's its immutable essence, every Block should be immutable. The hash function captures that. We all know that every Block contains the hash of the previous Block and how difficult it is to alter the Block's hash. But wait; is that all? How do we take the hash? Just pile up all the data and transactions (concatenate them) and take the resultant hash?

- Option A - hash all the data concatenated together

- Option B - Use Merkle trees

While both seem feasible, but virtually all the Blockchain platforms use option B. You may be wondering why?

Merkle Trees...The name seems familiar.

While Blockchains are disgraced for encumbering nodes with all data from inception, it is not always the case that Blockchains are purely fueled by full nodes. Like big brothers, full nodes carry the load of the network by downloading all data from the network and validating transactions. But light nodes (of Ethereum and Bitcoin) work on the mechanism of Merkle Proofs.

While piling up all the data side by side may work for immutability, it is not efficient when it comes to light clients.

Light clients work on a concept of Merkle Proofs that leverage incremental build-up of the hash of N elements' to determine the presence of a transaction inside a Block. Merkle proofs provide a lightweight mechanism that enables the light clients (who do not store the whole Blockchain data) to verify transactions with a tiny fraction of the actual Block data. This enables the light clients to run in-sync with the full nodes while verifying Blocks only with headers, obviating the need for full-scale verification.

Merkle proofs are based on a neat scheme devised by the famous computer scientist Ralph Merkle. The scheme involves creating a binary tree of data present at the leaf level, where each leaf is hashed to give the next level of nodes. Here onwards, a pair of data is concatenated and hashed to form its parent. This is carried on until there is a single root called the Merkle root. The Merkle root forms the single hash representing the entire data.

To verify the presence of a single data element, one does not need all the leaf nodes to calculate the root. This mechanism enables lightweight verification of the element by selecting a unique path called the Merkle proof corresponding to a leaf node (or element in question to be verified). Just select all the non-leaf nodes: the ommer (parent's sibling) nodes starting with the element, and then recursively until you reach the root. The nodes that path followed is the Merkle Proof of the element to be verified.

So imagine if there are N elements to be stored, the proof would be as long as the depth of the tree, i.e. log(N).

Vitalik Buterin has explained this concept in this article. I recommend reading it highly.

Although things in the Fabric world are not different in using Merkle Trees, Fabric does not have a concept of light clients. The reason Merkle Trees why Fabric adopts Merkle trees are for optimizing data storage on-chain. For example, range queries supported by fabric chaincode use Merkle trees to optimize storage of a range of keys read in a transaction.

So, now that we have questioned a few fundamentals about Blockchain. Let us discuss State and why it is so crucial to the Blockchain.

Blockchain was enough. Now, why this State?

The State is the snapshot of the Ledger from inception till now. Let us come back to the famous example of chess. The Ledger is the list of all the moves you and your friend made from the game's start. But the State is how the board looks since the last move was played. The State gives a way to interpret the present, considering all the transactions that happened since inception. Without the State, to know Alice's balance, one has to get the books rolling afresh. The State can be thought of as a set of key-value pairs at their latest condition; checkpointed using a version number.

The State Juxtaposition

Before we probe further into why Blocks tick the Blockchain and contrast the ledger platforms' Block structure, let us tour the mystery on how and why the State of Ethereum differs from that of Hyperledger Fabric.

The Merkle Patricia Trie - Magically storing State of Ethereum

Let us again go back to the Design Philosophy of Ethereum and Hyperledger Fabric. Ethereum is a public ledger and must store all details of all transactions that happened since inception. But do we really need to know how the past looks like? Even if we had to, we could always replay the transactions that appeared in each Block. Right? So, does it make sense to store all the history as State again?

Yes, and, Ethereum does store history State. The rationale is discussed later in this post. But think for a moment, it is a gargantuan task to store the history since inception - like recording every single moment of your life in a camcorder. How does Ethereum manage to store the entire history? 🧐

Ethereum... History of the State... 🤯 How?

The State of any system can be represented as a set of key-value pairs. In simple terms, keys can be account addresses, and value can be the balance. There are numerous mechanisms to store key-value pairs persistently. But storing the History state means storing a part of the State which was identical in the last Block and didn't change in the current Block, N times over. This is highly inefficient, and Ethereum researchers had a nifty trick up their sleeve. Most Blocks would only store redundant information that didn't change since the last Block. To ensure tamper resistance of the states, the researchers tied the Trie structure and Merkle Tree into a hybrid structure called Merkle Patricia Trie.

The Merkle Patricia Trie (MPT) isn't ordinary data structure. It is meant to solve multiple challenges at once.

- Save Space by reusing and referencing old state elements (KV pairs).

- Solve the problem of proving the non-existence of an element in the State - which is not possible with a regular Merkle Tree

- Quick search of keys. Max number of traversals is the tree's height (which is the length of the keys in this case).

- Establish provenance of state changes by hashing state elements into an N-ary tree (where N = 17) into a single root. (N is 17 is because each node can branch into 16 different hexadecimal elements, and one place is reserved for a value.)

Although somewhat cryptic, I will reuse the fantastic original visual representation of the Merkle Patricia Trie from Stack Exchange.

Although intimidating, the MPT is a relatively simple concept to understand. There are three essential components:

- Keys - The key is the reference to find the value. In Ethereum, Keys are User or Contract addresses. Addresses have specific values. But a lot of Keys(addresses) have the same prefix. To avoid too many branches, keys with the same prefix are grouped together like in a Trie.

- Values - A value can be a number like a balance, the code of a smart contract or transaction receipts. The smart contract internally maintains the State of contract in a separate Merkle Patricia Trie called the storage trie. We discuss the smart contract storage in a separate post.

-

Nodes - The unit of the tree. Each node is either an Extension node,Branch Node or a Leaf node.

-

Extension nodes - This is the divergent path node when key prefixes do not match. Each nibble (four bits) that correspond to the hexadecimal characters that match the Key prefix are stored as shared nibbles. In the example,

a7is the shared prefix for all the keys. So two nibblesaand7are stored at the root node a type of extension node. The next node is again a reference to a node, which can be either of an Extension, Branch or Leaf node. - Branch Node - This is where the nibbles start getting really wiggly and differ significantly. There are 16 references. Each of them points to a different node whose nibble matches the single corresponding sequence in the key.

- Leaf Node - The ultimate of the trie, which usually ends in one or more nibbles in the keys. It contains a value.

-

Extension nodes - This is the divergent path node when key prefixes do not match. Each nibble (four bits) that correspond to the hexadecimal characters that match the Key prefix are stored as shared nibbles. In the example,

The punchline is that if you follow each nibble in an extension node, each reference in a branch node, and the leaf node key-end nibbles - the path you trace is the Key nibble by nibble. The value is stored in the leaf node. You may end at an intermediate node - and if there is a value in any of them, then that corresponds to the key traced by the nibbles so far.

When a new Block is mined, and the current State is changed by the transactions in the Block, a new state root is formed. The new trie is constructed with the keys that changed in the transactions and reconstructing the entire state trie is avoided. Only the keys that change fork off to create a new part of the trie with new nodes, while part of the trie corresponding to the nodes where the keys did not change still refers to the old trie. In each Block, the State of the trie is a snapshot using a KECCAK256 hash function and stored as the state root in the Block header. This makes a lot of sense since there are millions of accounts in Ethereum that can change and reconstructing the entire State would be inefficient in terms of storage and computation.

The above diagram shows how the Merkle Patricia Trie changes from Block 654 when Dorothy(a77d379) transfer 0.01 ETH to Emily (a7ff377) who has just joined the network.

Ethereum History State, but why 😲?

In simple words, Ethereum faced vicissitudes of forks and understands the importance of decentralization. In case of a mishap (a fork), it would be a gigantic task to recompute the State of a historical state from inception. Keeping old states means that the chain can quickly switch back to a relatively sane State. But would it make sense to store all the State since its inception? Of course not, that would mean keeping the provision to rollback to the genesis Block in case of a catastrophe. 😅 Of course, this would not happen because that would mean Ethereum prices would crash overnight. There would be a mass exodus of believers of Ethereum. So, Ethereum stores the last 128 states as history and prunes the rest of them.

Can I query the history state?

Technically, one cannot query history. Still, events emitted by the Ledger are also stored on the Ledger and can be queried through Web3 APIs. However, querying the history state inside the smart contract itself is not possible. Ethereum does not allow the querying of the smart contract state because it prunes all historical States but the latest 128 Blocks.

Relax with the Couch State in Hyperledger Fabric

Unlike Ethereum, Hyperledger Fabric's State is quite simple. It uses a Couch database to store its ledger state. Couch DB is a document database where each document can be uniquely referred to by a unique key. Hyperledger Fabric allows the Smart contract developer to store keys (user-defined). These keys themselves form the State of the Ledger. Fabric also keeps track of the changes to a key. The approach is straightforward. It maintains a separate database that keeps track of all the keys changed and in what Block. It is then possible to query the history of that key using a Smart Contract API. Note that it is not the history state but a track of where the key has changed over time.

The Couch database, apart from offering a key value pairs also offer a rich NoSQL querying interface to query Key-Value pairs using Mango Queries. Those familiar with SQL like queries can relate and imagine life without them. Mango Queries helps you find the relevant documents (Key-Value pairs) of interest with a querying language. This speeds up the querying process without having to traverse through every key in the database.

The Block Recipe

Now that we have grasped an overwhelming lot about the State, I thank you for your patience and support for still reading. Let us now explore the Block of the Ledger. When talking about the fundamental structure of a Block, there are a few basics that all Block based ledgers follow. The Block would essentially consist of three things:

- The list of transactions

- The hash of the previous Block

- The Block number

In addition to this basic structure, each Block holds unique information about accountability. Accountability metrics answer the WHO of the Block.

- Who sent the transactions?

- Who proposed the Block or the Block creator?

These metrics for accountability play a key role in the security of the Blockchain. The sender of the transaction needs to be identified for obvious reasons. However, the Block proposer needs to be identified for incentivizing or penalizing the Block creator. In the last post, we discussed the need for stakes. In a Block creation mechanism, there needs to be a leader, identifying the leader is imperative to maintain the sanity and security of the network.

Block Structure Compared

Now that we know the lifeblood of the Block, let us trek further to understand the fundamental elements of the Ethereum and the Fabric Block.

Ethereum Block Structure

When it comes to Ethereum, being a public Blockchain platform has a lot of Block data. The header of the Block in Ethereum contains three essential elements.

- the essentials - This comprises what every Block in a Blockchain should have, i.e., the parent Block hash and the Block number.

- Block creator data - This contains the details about the Block creator, the reward information, the total gas expenditure, the total gas limit imposed on the Block, the total gas used and the timestamp at which the miner mined the Block. This is to essentially know who has mined the Block for its accountability and establish the traceability of the new ethers introduced into the Blockchain. Without this information, there would be no provenance of where the new ethers came from.

- proof-of-work data - This section essentially contains the proof that the miner has indeed mined the Block. This is the endorsement of the miner's work to mine new ethers into the system. Proof of Work (PoW) enables anyone to verify quickly and with ease - that sufficient computational energy has been spent to find the nonce that when hashed with the Block header hash (without the nonce) yields a value lower than a target. In other words, the miner did not introduce new Ethers out of thin air into the system with negligible or zero cost. This mechanism is detailed in the EthHash documentation.

data related to possible alternate chains - Since Ethereum rewards competing miners who have solved the PoW challenge unlike Bitcoin, it is also necessary to keep accountability and provenance of the money introduced through the route of alternate chains. However, there is a caveat that Blocks that are introduced by Ommers (or uncles) can be referenced only till six Blocks from the Block of introduction. The reason for this is simple.

Since Ethereum chooses the main chain by using GHOST (Greedy Heaviest Observed Sub Tree) protocol, there can be multiple parallel chains. If these chains grow too long, it would be extremely inefficient for the Blockchain to search and reference data during validation time. Imagine the Blockchain turning into a giant tree with ever-growing depth. It would be inefficient in traversing an unbalanced tree which is too deep to search. Along with the GHOST protocol restriction, the six-Block reference imposes an incentive to mine only on the longest chain.-

state-related data - Ethereum keeps track of the State as well to ensure that states are consistent and non-repudiated across all Blocks. There are types of states.

- State Root - This is the MPT root of all the state changes in the current Block. This includes changes in State of user and contract accounts.

- Transactions Root - The MPT root of the transactions that were confirmed in the Block. Again MPT to the rescue to optimize storage and depth of the Merkle Tree.

- Receipts Root - The MPT root of the transaction receipt (the receipt you get after every transaction in Ethereum).

The rest of the blocks just contain signed and validated transactions that the miner has accumulated and proposed as the block content. Each transaction holds information about the sender and the receiver of the transaction. In all cases, the sender (from) is the User address, the receiver (to) is user in case of direct Ether transfer or a contract in case of a contract invoke or a call. Contract invokes write data on the ledger, while calls just read. The value is the amount of ethers the user wants to send, while the data is applicable for contract calls to store calldata.

Hyperledger Block Structure

The Hyperledger Fabric Block looks different but contains some similiar characteristics as that of Ethereum.

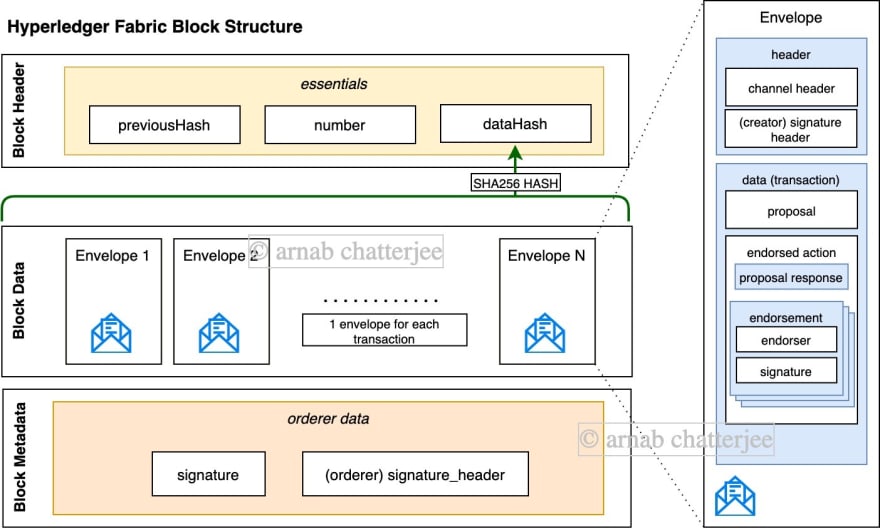

- Block Header - Let us start with the Block Header. It contains the essentials - previous Block hash, the Block number and the data hash. The data hash is principally the hash of the transactions in the Block wrapped in an Envelope. The Envelope is an overarching concept of the transaction that we will explore soon.

-

Block Data - The Block data is a collection of Envelope; each wrapping a transaction. An Envelope contains more than the transaction proposed. But why enclose more data? Remember Part 1 of the article and how Fabric doesn't need to vet the transaction with all the participants in the network. To guarantee accountability and correctness, the transaction is send first as a proposal to interested parties in a channel for verification. And these participants are a part channels, the channel information is stored as well. So in a nutshell, the Envelope contains.

- Header - Information about the channel and the creator of the transaction along with the signature.

- Data - Information about the transaction proposal, the endorsed response, along with the endorsements (signatures) of the stakeholders who endorsed the transaction proposal response.

The endorsements capture the consent of the stakeholders in the transaction's outcome (validation). This furthers the accountability of the stakeholders in the transaction. We will discuss the details on Transaction flow including endorsements in a future article.

Well, that is all. Thank you for reading so far in the journey to explore the Architectural rationale of Blockchain Platforms. We discuss Identity management of Blockchain Platforms and the rationale behind decisions in the next article. Thanks again and stay tuned.

Top comments (0)