Summary

I have started a new project on Github called 'Guides'. It is a repository of technology guides that will be written by me. The reason I created this project is because I learn more when I write about a topic. It also helps solidify or clarify concepts. I will be continuously updating these guides and they will never be complete. The goal is to make the guides as accurate as possible. However, I won't always get it 100% correct and will rely on feedback from the community to improve or correct where applicable.

The first guide that I've started is a guide on Docker. I chose Docker as my first guide because I think that of all the trending technologies circa 2018, Docker is one of the most interesting, important and applicable technologies to anyone involved with the software development/deployment. Therefore, whether you're writing software (frontend or backend) or whether you're managing the operational side of software deployments, Docker can help you do things better.

In this post, I present the first part of my Docker Guide, the Overview. In this first part I discuss the backdrop of Docker and it's associated technologies.

Please find the original work at the following locations:

All future updates will be to the github project repository.

Overview

It is important to understand the backdrop and what ultimately lead to Docker and it's success. Therefore, in this guide, I am going to explain a few topics that relate to the challenges of application life-cycle and how Docker can help address those challenges. Firstly, I will discuss some of the problems associated with application life-cycle and why we need a better way of running applications. Secondly, I will discuss Docker, its associated technologies, and how Docker helps us run and manage applications better.

The Challenges of Software Deployment

In this section, I will discuss some of the challenges associated with deploying and running applications.

The whole point of a computer is to be able to run applications on it. Before virtualization, there would typically be a physical computer system like a server onto which all applications could be installed. Each physical computer system would have its own operating system (OS). All applications would need to be compatible with the OS that they're being installed on. The OS would need to support multiple applications by having multiple runtimes, frameworks, libraries, configurations and security implementations. Furthermore, the OS would also need to be of a particular version that all applications support. Any patch, upgrade, or install on the OS has the potential to break other applications. Although all applications run within their own processes, the default isolation associated with each process isn't enough to help ensure the integrity and reliability of the OS and it's underlying applications. Instead of being a solid and clean runtime that supports the running of all applications, the OS becomes a big ball of mud. This basically means that the OS becomes less cohesive and increasingly coupled to other dependencies that result in a system resembling "spaghetti" where there is no clear separation of concerns. Therefore, when one considers what actually goes into getting an application into production, then one begins to realise how difficult it actually is. It's even more challenging when supporting multiple deployment environments (dev, test, staging). Therefore, the challenge that we face, is how to get an application all the way from development into various deployment environments, in a automated, consistent and error-free manner. This challenge can be further deconstructed into more specific challenges namely distribution, installation, and management. I call this the ”DIM (Distribution, Installation, Management)” model. In the following paragraphs I will be discussing DIM and any associated problems.

I would like to note that the following challenges are proportional to scale. As a small team with a few small applications, the following challenges may not seem a challenge at all. However, as ones deployment architecture grows in complexity, so does the complexity associated with DIM. Complexity is either by design or by accident. And if it's by design, then it's because you haven't understood the problem well enough. By finding better ways to do DIM, we help reduce overall complexity through better practice and design.

Distribution

Distribution of applications is complicated and difficult. There is an entire process or workflow that one needs to determine in terms of how to deliver an application from development into test, staging and production. The process will be different for each software development and operations environment. Here are some questions that one should be asking:

- How will application be packaged?

- Will application need to be discoverable?

- Will application need to be downloaded?

- Is distribution a simple matter of copying files across to next destination?

- What security implications are associated with distribution? For example is there any sensitive data that needs to be distributed as part of application distribution? Should application and/or configuration be encrypted? Does one require hash codes to help ensure the integrity of application being distributed?

- How are updates and patches for different applications distributed?

- How many environments does application need to be deployed to?

- Can continuous integration (CI) and continuous delivery (CD) be used? If so what does that look like and what skills are required?

- How do we do change control? How do we make change control simpler and easier?

With all things considered, a simple task of getting an application from a developers machine (actually this should be from your distributed version control system) into test or production, can turn out to be daunting. The problem only gets more challenging the bigger the organisation and number of applications.

Installation

Even as a developer, I have had to endure a fair amount of time in the trenches of software/application installation. Needless to say, installation of applications can be a slow, error prone, tedious, and frustrating task. In software development circles there is an analogy of a gorilla holding a banana and is usually used to explain the "n+1" problem related to ORM (Object Relational Mappers). I am going to use that analogy here because I think that it also applies. Think of the application as the banana. For installation, all we want is the "banana". But we don't get the banana. Instead, what we get is the banana, the huge angry looking gorilla holding it, all of the gorillas tribe, and the entire jungle that it lives in. I think you get the point. It's essentially an "n+1" installation issue. Most applications come with a bucket load of dependencies (and each having their own set of dependencies).

Here are some more problems associated with installation:

Not all applications are cross-platform meaning that not all applications can run on all or multiple operating systems. This results in a need for multiple physical computer systems with different operating systems to run relevant applications.

Often applications would need to run on similar ports resulting in port conflicts. These conflicts would also only be detected once the applications have been installed and started.

After deploying applications, there would usually be some configuration that would need to take place to ensure the correct functioning of the application being installed. This additional configuration step is prone to error (like missing a step or misconfiguration) and security issues (like plain text passwords).

All applications have different requirements in terms of their dependencies. Therefore, one would need to install numerous libraries and frameworks in order for an application to install and run correctly. This usually resulted in library and framework conflicts where often the only solution would be to install the application on its own physical computer system with its own set of libraries and frameworks.

Security in this model is full of vulnerabilities (anything with a potential for damage or loss). One example, is that often sensitive information that is required as environment variables would be stored in plain text, and this would be available for anyone to see that managed to gain access to the computer.

When new applications are deployed, or when a computer system needs to be patched (software and security updates), there would almost always be downtime associated with it.

Furthermore, one of the biggest problems faced with installation is that all applications come with baggage and requirements which are often at odds with the deployment destination. It's why we're all too familiar with the "But it worked on my machine" excuse. Additionally, applications tend to be fragmented instead of cohesive. It's also why installation documents/guides are required to detail each step of the way. But these install documents are often poorly written and/or incomplete. Documentation is also seldom updated.

Management (Operation)

At this point we have distributed and installed our application. But how do we manage our application and it's increasing resource requirements? One could write books on this stuff. However, I am going to only mention a few of the problems that I think are most common when it comes to managing an application. They are also problems that virtualization technologies can help address.

Here are some operational problems that one may encounter when managing applications in different environments like test, staging, and production.

Applications resource requirements grow over time. This means that an application may need more processing power, more memory (RAM) or more hard disk space for example. Therefore, one could scale the system using either Vertical Scalability or Horizontal Scalability (Scalability). For the most part, it has been easier to employ Vertical Scalability due to most applications inability to work in a distributed fashion. The result would be adding either too much or too little resources which ultimately lead to wasting of money and/or computing resources.

The problem of horizontal scaling (without virtualization) is that one is required to build a separate physical machine. This takes time (often a debilitating lead time) and large sums of money to execute. And often an application may only need additional computing power at peak times (like black friday for example). Then when traffic decreases, you're left with an uber computing machine doing nothing except wasting resources and money.

Simple application life-cycle operations like starting, pausing, stopping, and restarting an application is either very difficult or not possible at all.

Sometimes an application could go rogue as a result of one of it's processes going into an infinite loop for example. A rogue application can bring an entire computer system to a halt if left unchecked.

Redundancy can be achieved with physical machines but it's very expensive and once again suffers from under utilization. And even if one were using virtual machines, the time it takes to spin up a new virtual machine can take quite long. Being offline for anything more than a few seconds is not acceptable and in some cases, life critical.

All of the problems mentioned above are compounded when one is required to setup multiple environments like dev, test, staging, production. And it gets even worse if you have a multi-tenant environment where each client requires their own setup. Couple that to a multitude of applications with a multitude of varying dependencies and you have the perfect storm.

Now that we understand some of the challenges associated with application deployment life-cycle, in the next section I am going to discuss Docker and how it has emerged to become one of the hottest technologies of our time.

Docker

The solution to overcoming the challenges presented above has been to use virtualization technology like virtual machines (made possible through hypervisors). However, virtual machines were the first step on the path to deployment utopia. Containers are the next step of the deployment evolution. This is also the point at which Docker emerged and changed the way we work with containers forever.

Often, the terms Docker and containers are used interchangeable as though they're the same thing. However, Docker is not a container and nor did Docker invent the concept of containers. Containers have been around for more than a decade, and the idea of containers a lot longer (History Of Containers). Docker is a classic example of "Standing on the shoulder of giants". Containers are inherently difficult to work with and manage. Therefore, Docker came along and took a difficult to understand (and work with) technology and put it into reach of mere mortals. Docker is a container management system that makes container management easy.

To further understand what Docker is, it is important to understand the following key topics:

- Virtual Machine

- Image

- Container

- Virtual Machine / Container Comparison

- Registry

- Repository

Virtual Machine

In the previous section I discussed some of the challenges related to application life-cycle. A big part of the problem has been having to work within the bounds of physical computer constraints. These challenges gave rise to hypervisor technology that enable us to create virtual machines. Because containers are often compared to virtual machines, I would like to explain what the differences are to help reduce or avoid any confusion between the two.

What if one could create a sort of "vertical slice" of a physical machine. Each slice would be allocated a percentage of the physical machines resources. Therefore, one could then install a specific operating system to each slice to satisfy the application/s requirements. This sounds great in theory, but one can't very well take a knife to a physical machine, divide it into bits, and expect it to still work. Not in the physical world anyways. Enter virtualization and the hypervisor. A hypervisor helps us divide our physical machines into virtual computing "slices". And though hypervisor technology is by no means a panacea, it goes a long way to help address some of the challenges mentioned above. A hypervisor helps us create virtual machines. A virtual machine is an emulation of a physical computer system in that it virtualizes physical computing resources like CPU, RAM, Network, and Disk.

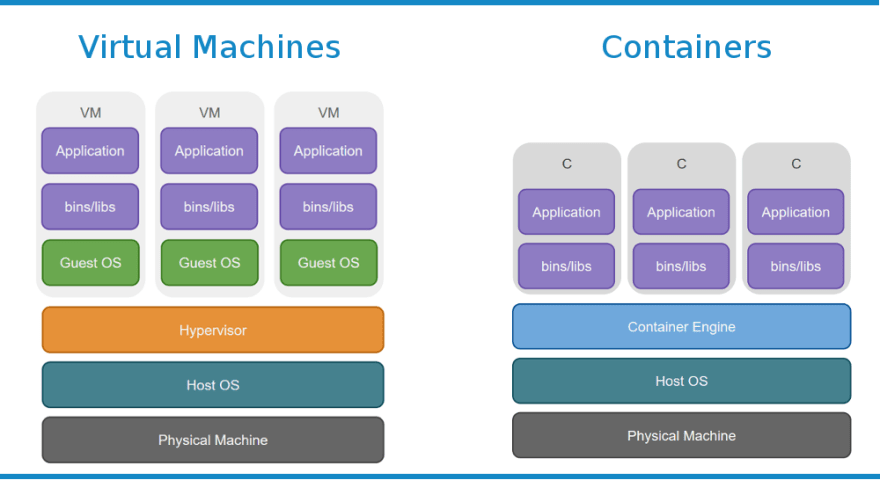

Let's look at a conceptual diagram of virtual machine technology.

As can be seen from the diagram above, we have 3 "slices" of a physical machine where each slice is a virtual machine. An important takeaway is that virtual machines require their own guest operating system. In the diagram, I am also illustrating a "Type-2 hosted hypervisor". This means that the hypervisor runs on a conventional operating system. The other type of hypervisor is the "Type-1 bare metal hypervisor". These hypervisors run directly on hosts hardware without the need for a host operating system.

Image

An image is a file (a binary representation of what a container should look like). Conceptually an image is a template (blueprint) for creating containers. In fact, a lot of the time when containers are mentioned, it is actually images to which is being referred. However, containers are a "run-time" thing whereas images are a "build-time" thing. The analogy that I like to use is a concept taken from object-oriented programming (OOP). In OOP, two of the most important concepts to understand are classes and objects. A class is a template(blueprint) and they are used to created objects at run-time. An object exhibits all the properties and behavior of a class except it only exists at run-time. Like a class, an image is used to create containers that represent a running instance of that image.

Therefore, if one wanted to run an instance of MongoDB or Elasticsearch on your host machine. Why not instead use one of the ready made images that are available via the official Docker registry (more on registries to follow). The images can be located at the following locations:

Remember, images are used to run containers. Therefore, a MongoDB image will be used to run a MongoDB container for example.

Container

Think of an operating system with a whole bunch of processes running within it.These processes share just about everything (CPU, memory, network etc) and every process knows about every other process. But what if you want to run one or more processes within an isolated “sandbox” environment? The sandbox would provide isolation and allow each process to have its own process namespace for example. Furthermore, the sandbox would be able to control and limit the capabilities in terms of how much resources may be used by the process.

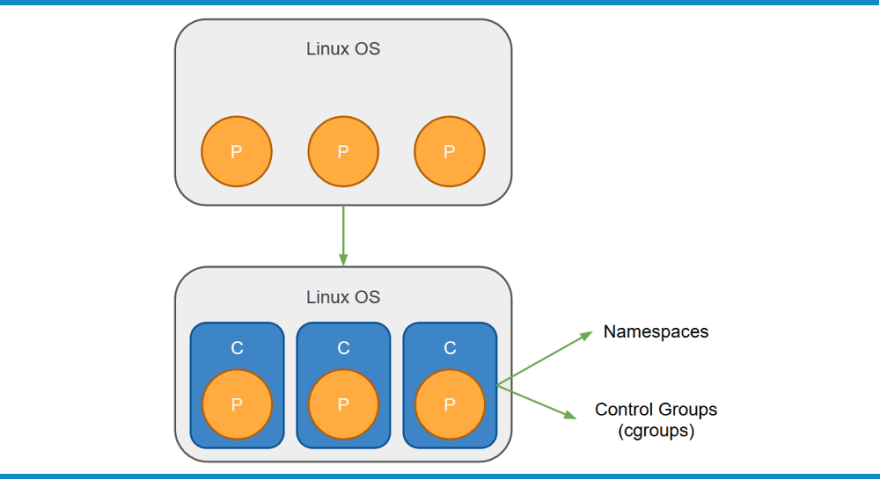

It is the notion of an isolated process in a "sandbox" that gave rise to container technology. The “sandbox” that I have been discussing is what we have come to know as the container. Containers are isolated processes that virtualize an operating system. The mechanisms that make this possible are known as "namespaces" and "control groups (cgroups)".

As one can see from the image above, we initially started off with a Linux OS. I use Linux because the genesis of container technology all happened on the Linux OS. Each process has no (or very little) isolation. Through the use of namepsaces and control groups, we are now able to run each process as an isolated process in it's own container.

Namespaces

The official documentation for namespaces states the following:

A namespace wraps a global system resource in an abstraction that makes it appear to the processes within the namespace that they have their own isolated instance of the global resource. Changes to the global resource are visible to other processes that are members of the namespace, but are invisible to other processes. One use of namespaces is to implement containers.

Therefore, namespaces provide process isolation by allowing each process to run in it's own isolated workspace. Therefore, when one runs a container, the following namespaces are created for the various facets of a container.

- IPC - Isolates and manages access to IPC

- Network - Isolates and manages network devices, stacks, ports etc.

- Mount - Isolates file system mount points

- PID Namespace - Provides process isolation

- User Namespace - Isolate user and group id's

- UTS Namespace - Isolate hostname and NIS domain name

Control Groups (CGroups)

The official documentation for cgroups states the following:

Control cgroups, usually referred to as cgroups, are a Linux kernel feature which allow processes to be organized into hierarchical groups whose usage of various types of resources can then be limited and monitored. The kernel's cgroup interface is provided through a pseudo-filesystem called cgroups. Grouping is implemented in the core cgroup kernel code, while resource tracking and limits are implemented in a set of per-resource-type subsystems (memory, CPU, and so on)

Therefore, cgroups are all about organizing processes so that resources can then be allocated to them.

Virtual Machine / Container Comparison

Containers are not mini-virtual machines, and they're not like virtual machines. This should be clear from my discussion above. However, to help further clarify the meaning of containers, I provide a further comparison between virtual machines and containers as can be seen below.

From the diagram above, the differences between virtual machines and containers can be summarized as follows:

- Where a hypervisor virtualizes the physical computing system (hardware), containers virtualize the operating system.

- Where a hypervisor abstracts the operating system from the hardware, containers abstract an application from the operating system.

- Where virtual machines need their own guest operating system, containers share the host operating system. This is why, in order to run Linux containers, you need a Linux host operating system. And you will need a Windows operating system to run Windows containers.

Furthermore, virtual machines and containers are also not opposing technologies. They can in fact be used as complimentary technologies. This is how Windows and Apple have managed to offer Linux containers on their platforms. Both Windows and Apple operating systems require a hypervisor to run a virtual machine with a Linux operating system (Alpine) so that one can use a technology like Docker to host Linux containers. Although, Windows has made significant progress in terms of their container offering. As of the time of this writing, one can choose whether to use Windows or Linux containers on a Windows (Windows 10 Pro) operating system.

Containers also do not replace virtual machines. Although there are many scenarios where using containers would be better (microservices for example). As mentioned above, the two technologies are quite different. Remember, virtual machines are all about virtualizing hardware, and containers are all about virtualizing the operating system.

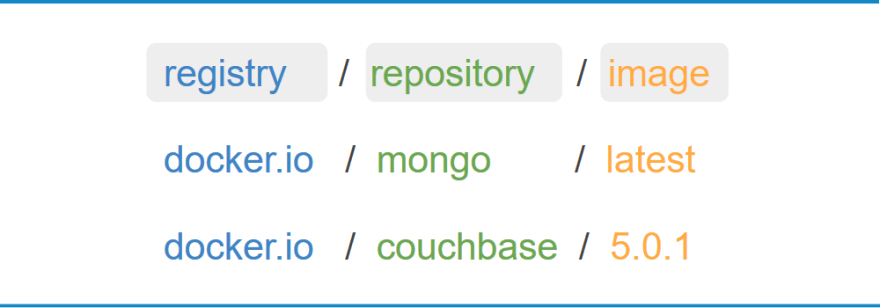

Registry

A registry at it's most basic level is a place where one can store and retrieve Docker images. Docker provides both public and private registries and can be found here. If you've ever worked with software development package managers like NPM or Nuget. Or if you've worked with linux package managers like DPKG or RPM. Then the notion of working with Docker registries should feel familiar.

Docker isn't the only platform that offers Docker registries. Microsoft Azure, Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud Platform, Digital Ocean are but a few of the alternative Docker registries that are on offer. One can also host on-premises registries using Docker Trusted Registry for example.

For more information on Docker registry, please view the official Docker documentation here

Repository

A repository is the actual location of where specific images can be found within a Docker registry. This is further clarified in the diagram below.

Summary

I have discussed what I perceive to be the primary challenges associated with software deployment. The key takeaway from that discussion is that we need a better way to deploy software applications. And by deployment I refer to everything relating to distribution, installation, and management (operation) of software applications. We desire software applications that are more portable, cohesive, independent, and isolated from other applications/processes. This enables us to reduce the complexity and errors associated with software deployment. And this results in more robust, secure, and easier to scale software applications.

Hypervisor technology allows us to create virtual machines (VM) whereby we can isolate our applications and manage our applications independently. One of the problems associated with VM is that they consume a lot of host resources. That's partly because each VM is required to have it's own guest operating system. Starting up a VM is relatively fast when compared to starting up (or preparing) a physical machine. However, when compared to startup time of a container for example, containers are exponentially quicker. One of the other problems relating to virtual machines is that they are not as portable as containers.

As I mentioned before in this guide. Containers are the next step in the evolution of application deployment. However, containers are difficult to understand and work with. Therefore, Docker emerged as a technology to make managing containers simpler. Containers allow us to package our applications into single cohesive, isolated, and portable packages that can be easily moved between different deployment environments.

Top comments (12)

A very nice and clear article.

I use docker every day, but never took the time to understand it fully. This helps a lot! Thank you

It's encouraging to hear that someone with an experienced hand found this useful. Thanks for the feedback.

I briefly knew about Docket and how it works but now I get it. I guess its time to start using Docker even for my private micro projects. thanks for the article!

Glad to hear you found it useful. I highly recommend using Docker for your projects. It's a good feeling when you can open a terminal window in your project directory, type "docker-compose up", and your entire dev environment spins up for your project :)

This is a great article, I like how you explained everything. I played with docker some time ago but didn't know all this, waiting for more.

Thank you for the positive feedback! I'm continuously updating my docker guide (and other guides too) content on github. It's great to hear that you've played with Docker. That's how it started out for me too. However, Docker has now become core to my development environment. For example, I no longer install databases (SQL and NoSQL) locally. Nor do I install web servers (apache and nginx) locally. I try to run as much as possible from containers. This has resulted in my dev machine always being clean and isolated from all these other software packages. It has allowed me to experiment with different versions of various programming runtimes or database versions without having to install/uninstall/reinstall a single thing. Therefore, I encourage you to play more :)

Great article, thanks.

This was very helpful! Thank you.

Thanks for the explanation, very easy to follow and understand!

I have just started learning docker and this has clear a lot of doubts for me.

Thank you for writing such a well explained article.

Great article.